The Labour Theory of Value

- Sangobarto Basu

- May 2, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 3, 2021

The labour theory of value is a major pillar of traditional Marxian economics, which is evident in Marx’s masterpiece, Capital (1867). The theory’s basic claim is simple: the value of a commodity can be objectively measured by the average number of labour hours required to produce that commodity.

If a pair of shoes usually takes twice as long to produce as a pair of pants, for example, then shoes are twice as valuable as pants. In the long run, the competitive price of shoes will be twice the price of pants, regardless of the value of the physical inputs.

Although the labour theory of value is demonstrably false, it prevailed among classical economists through the mid-nineteenth century. Adam Smith, for instance, flirted with a labour theory of value in his classic defence of capitalism, The Wealth of Nations (1776), and David Ricardo later systematized it in his Principles of Political Economy (1817), a text studied by generations of free-market economists.

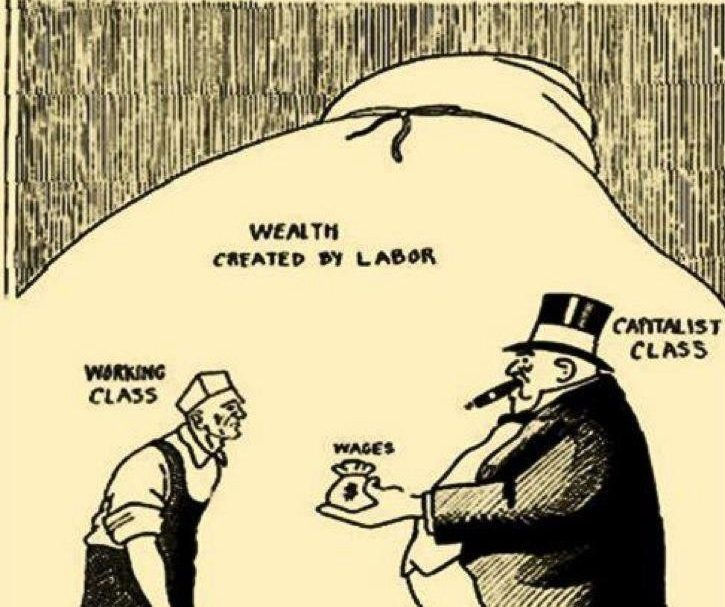

So the labour theory of value was not unique to Marxism. Marx did attempt, however, to turn the theory against the champions of capitalism, pushing the theory in a direction that most classical economists hesitated to follow. Marx argued that the theory could explain the value of all commodities, including the commodity that workers sell to capitalists for a wage. Marx called this commodity “labour-power.”

According to Marx in his Capital Vol-1, he initiated the concept of commodities in Chapter 1 which demonstrates that the commodity is, in the first place, an object outside us, a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of some sort or another. The nature of such wants, whether, for instance, they spring from the stomach or from fancy, makes no difference neither are we here concerned to know how the object satisfies these wants, whether directly as means of subsistence, or indirectly as means of production.

According to Marx every useful thing, as iron, paper, &c., maybe looked at from the two points of view of quality and quantity. It is an assemblage of many properties, and may therefore be of use in various ways. To discover the various uses of things is the work of history so also is the establishment of socially recognized standards of measure for the quantities of these useful objects. The diversity of these measures has its origin partly in the diverse nature of the objects to be measured, partly in convention.

We have seen that when commodities are exchanged, their exchange-value manifests itself as something totally independent of their use-value. But if we abstract from their use-value, there remains their Value as defined above. Therefore, the common substance that manifests itself in the exchange value of commodities, whenever they are exchanged, is their value. The progress of our investigation will show that exchange value is the only form in which the value of commodities can manifest itself or be expressed. For the present, however, we have to consider the nature of value independently of this, its form.

A use-value, or useful article, therefore, has value only because human labour in the abstract has been embodied or materialized in it. How, then, is the magnitude of this value to be measured? Plainly, by the quantity of the value-creating substance, the labour, contained in the article. The quantity of labour, however, is measured by its duration, and labour time in its turn finds its standard in weeks, days, and hours. Some people might think that if the value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of labour spent on it, the more idle and unskillful the labourer, the more valuable would his commodity be because more time would be required in its production. The labour, however, that forms the substance of value, is homogeneous human labour, expenditure of one uniform labour-power. The total labour-power of society, which is embodied in the sum total of the values of all commodities produced by that society, counts here as one homogeneous mass of human labour-power

, composed though it is of innumerable individual units. Each of these units is the same as any other, so far as it has the character of the average labour-power of society, and takes effect as such; that is, so far as it requires for producing a commodity, no more time than is needed on an average, no more than is socially necessary. The labour-time socially necessary is that required to produce an article under the normal conditions of production and with the average degree of skill and intensity prevalent at the time. The introduction of power-looms into England probably reduced by one-half the labour required to weave a given quantity of yarn into cloth. The handloom weavers, as a matter of fact, continued to require the same time as before; but for all that, the product of one hour of their labour represented after the change only half an hour’s social labour, and consequently fell to one-half its former value.

Capitalists, Marx answered, must enjoy a privileged and powerful position as owners of the means of production and are therefore able to ruthlessly exploit workers. Although the capitalist pays workers the correct wage, somehow—Marx was terribly vague here—the capitalist makes workers work more hours than are needed to create the worker’s labour power. If the capitalist pays each worker five dollars per day, he can require workers to work, say, twelve hours per day—a not uncommon workday during Marx’s time. Hence, if one labour hour equals one dollar, workers produce twelve dollars’ worth of products for the capitalist but are paid only five. The bottom line: capitalists extract “surplus value” from the workers and enjoy monetary profits.

Although Marx tried to use the labour theory of value against capitalism by stretching it to its limits, he unintentionally demonstrated the weakness of the theory’s logic and underlying assumptions. Marx was correct when he claimed that classical economists failed to adequately explain capitalist profits. But Marx failed as well. By the late nineteenth century, the economics profession rejected the labour theory of value. Mainstream economists now believe that capitalists do not earn profits by exploiting workers. Instead, they believe, entrepreneurial capitalists earn profits by forgoing current consumption, taking risks, and organizing production.

if you want to support us, consider following us across our social media handles. The links of the same are given below:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/p/CNz32hNpMEV/?igshid=in3117ucyfwk

Twitter: https://twitter.com/IndianTeenSoci1/status/1383791404808167426?s=19

Comments